Summary:

ChatGPT’s agent successfully booked a restaurant reservation. But the process was time-consuming and vulnerable to misunderstandings and errors.

OpenAI recently released its agent mode for ChatGPT. Agent mode enables ChatGPT to navigate and manipulate websites designed for human use. This article documents my first impressions of this new interaction paradigm.

While this tool represents a significant step towards mainstream AI-agent use, my simple evaluation revealed that agentic AI still has a long way to go.

The Task: Book a Business Lunch

Watch a recording of this interaction (about 5 minutes). This is a ChatGPT replay of this agent interaction; it’s sped up and does not depict the actual duration I experienced.

I chose the everyday task of booking a restaurant reservation. This was my starting prompt to ChatGPT:

Find a restaurant suitable for a business lunch near 3100 Travis St, Houston, TX 77006 for next friday at noon.

Is this a high-quality prompt? No.

I kept it terse and deliberately omitted relevant details to simulate real-life use of everyday people who don’t fancy themselves as “prompt engineers.” (Writing highly detailed prompts poses a high interaction cost on users. In some of our recent studies of the prompting strategies of consumers, we’ve noticed that even experienced genAI users rarely include sufficient context and criteria in their first prompt.

Remember that the computer should adapt to the needs of the human, and not the other way around. I wanted to evaluate what this agent could perform with minimal handholding from a rushed and distracted user.

This realistic-yet-weak prompt should have encouraged ChatGPT to request additional details before beginning. For example:

- What does “suitable” mean here? Are you going to talk with a prospective job applicant and want a quiet venue? Are you trying to impress a client’s executive staff with something fancy?

- What’s the budget for the meal? Is this a casual lunch with a peer, or an expensive celebration?

- How will people be arriving? What’s more important: ample parking or access to mass transit?

- What type of food? Do attendees have preferred cuisines or dietary restrictions?

- How many attendees? Is this a 1-on-1 meeting, or will you need to rent out a private room in the restaurant?

Instead of asking any of these clarifying questions, ChatGPT jumped immediately into the task with limited context. It focused on the necessary geographic proximity and operating hours but didn’t ask followups on relevant topics that would have significantly influenced its subsequent searches and suggestions. This behavior struck me as unusual, since ChatGPT’s “deep research” mode always asks clarifying questions before investing 8–15 minutes researching and writing a report.

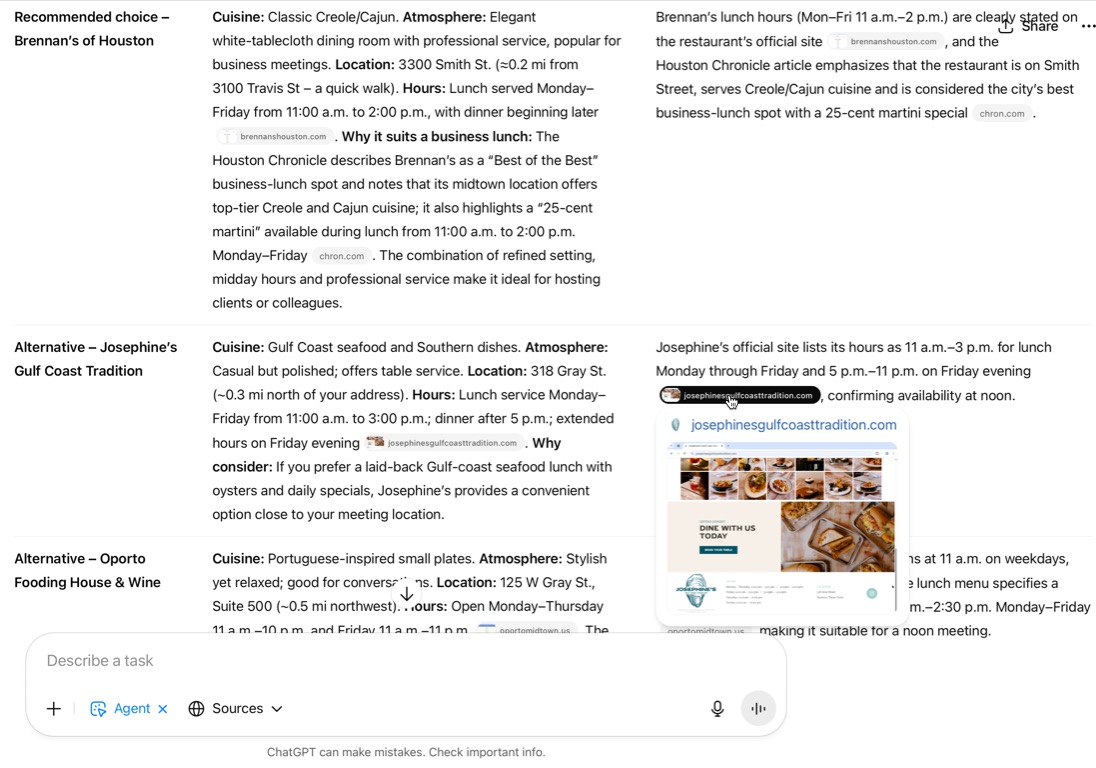

Step 1: Search for Restaurants

ChatGPT spent 6 minutes conducting research on various restaurants by performing 10 web searches utilizing 96 sources — far more than any human could reasonably use to find a lunch spot for a business meeting. (Though, arguably, a human might not need to consult 96 different sources to make a well-informed decision.)

ChatGPT’s search used mostly sensible sources for the task: Yelp, OpenTable, Instagram, and various restaurant-focused sites, and it took screenshots to document the process. ChatGPT did mention encountering some difficulties using these sites, such as dynamic features, anchor links that interfered with scrolling, and even the dreaded popup-upon-arrival.

Excerpts of ChatGPT’s documented “thinking” during this process:

The open table [sic] might be inaccessible due to dynamic features or cross-late issues. I’ll use the computer tool to open it and bypass these limitations.

It seems that scrolling has not progressed as expected, likely due to an anchor.

A pop-up about Oporto is showing, and I need to close it by clicking the ‘x’. I’ll use the multi-action function to click the cross and close the pop-up window.

ChatGPT eventually suggested 3 restaurants that are viable candidates for a business lunch, based on my expertise as a Houston local. It created a table containing the following information:

- Cuisine category

- Atmosphere

- Location (with distance from prompted address)

- Business hours

- Justification

There are a few glaring omissions in this list, though: What’s on the menu and how much will it cost?

It would be hard to choose a restaurant based on this information alone, and navigating directly to the restaurant’s website was a little difficult. Sometimes the embedded sourcing pills would link to the mentioned website, but, if the source was a screenshot, it would instead display an image preview that, when clicked, included a link to the website. I found this inconsistent behavior unintuitive.

These screenshots are an effective sourcing technique (an important tactic for trust building with users, which we discuss in our course Designing AI Experiences), but more direct access to the websites would have been helpful.

Step 2: Access the Restaurant Website

I responded to this table with a choice and direction:

Let’s book a table at Brennan’s.

After I prompted with the desired restaurant, ChatGPT spent a surprising 55 seconds attempting to access the restaurant’s website. It appears it was redirected to a Google Maps page, but it resolved this issue on its own.

Step 3: Clarify the Guest Count

ChatGPT then determined that clarifying the guest count was important before proceeding.

I replied with 2 guests but then decided to add a twist: I mentioned that 1 had a shellfish allergy. (Remember, typical users won’t behave methodically and logically! In these agentic interactions, they’ll likely share information whenever it occurs or is asked of them. And they still might not answer with total clarity. I didn’t tell ChatGPT who had the shellfish allergy, and it didn’t ask.)

Step 4: Book the Reservation

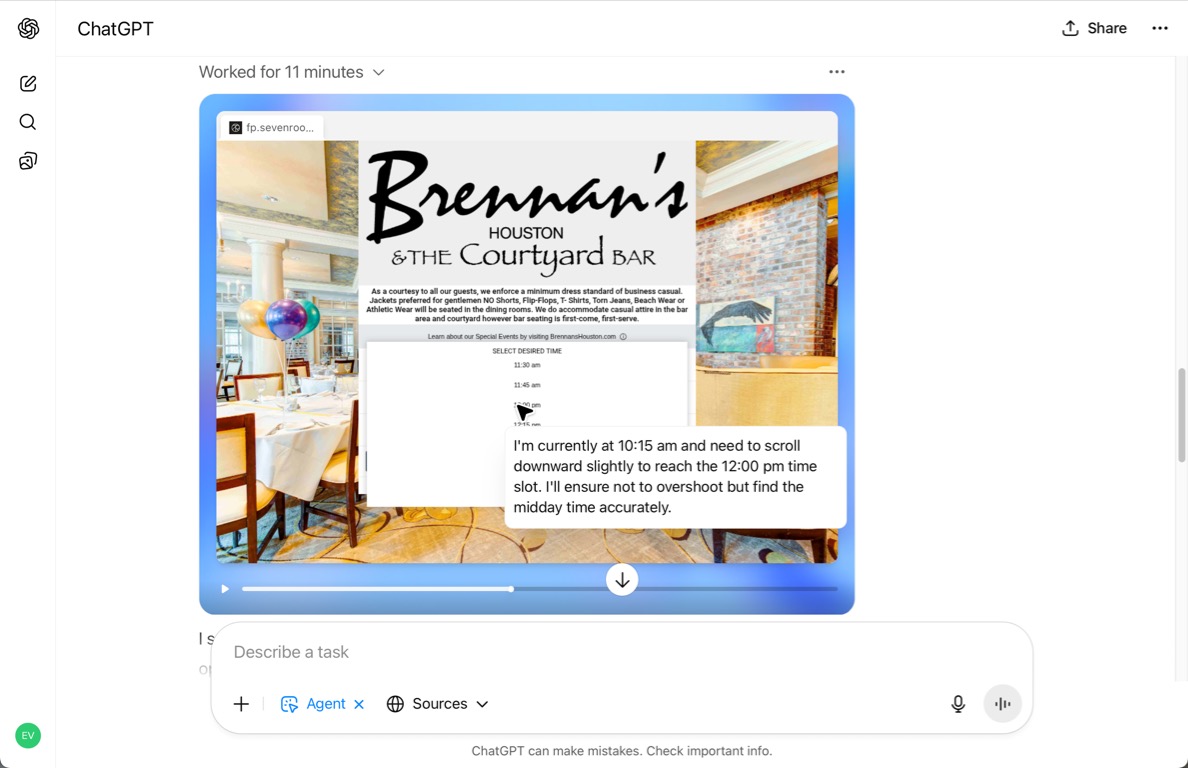

With the restaurant selected, guest count confirmed, and website open, ChatGPT was ready to book the reservation. This step was the most surprising step for several reasons.

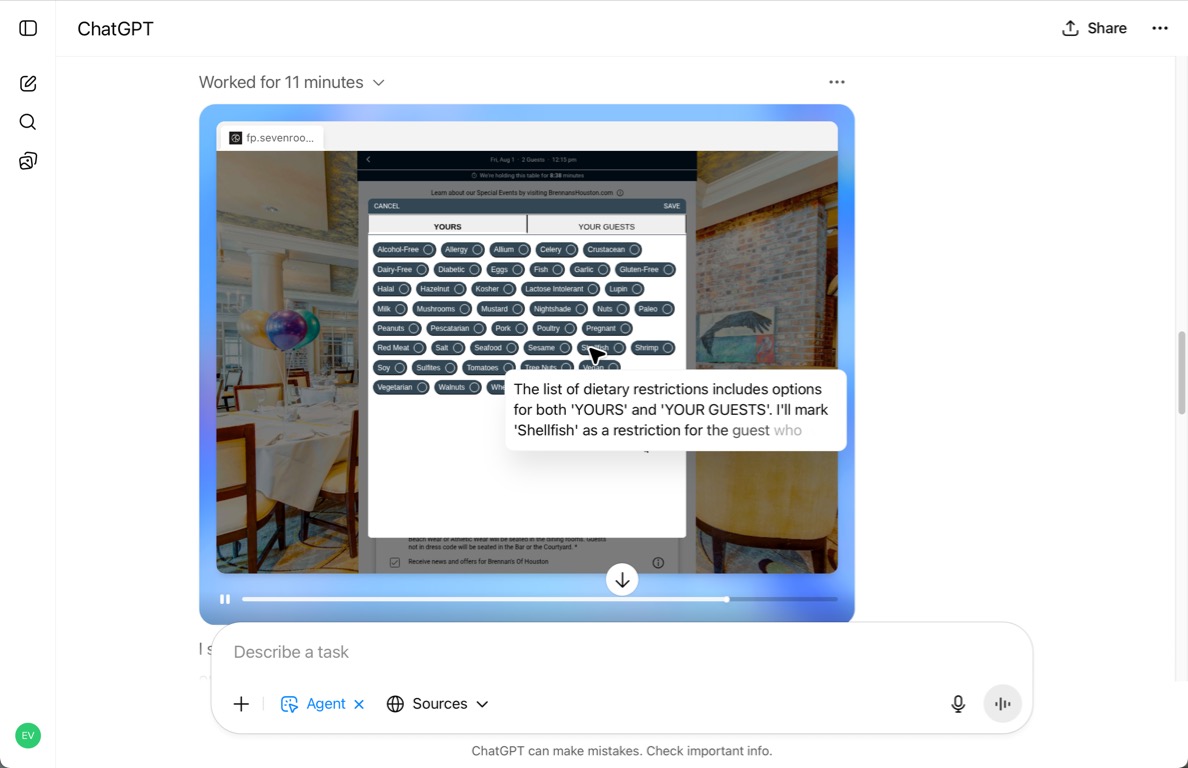

First, it took an unusually long time. ChatGPT needed 11 minutes to navigate the restaurant’s web forms, whereas it took me about 2 minutes to perform the same workflow at a casual pace. (Not exactly the magical time saver that AI agents are often purported to be.)

ChatGPT took so long to complete the process that the 10-minute window to hold a table reservation technically timed out. Fortunately, the website processed the reservation anyway, but if the restaurant had been receiving lots of reservations, it could have been rejected and the process would have needed to pivot.

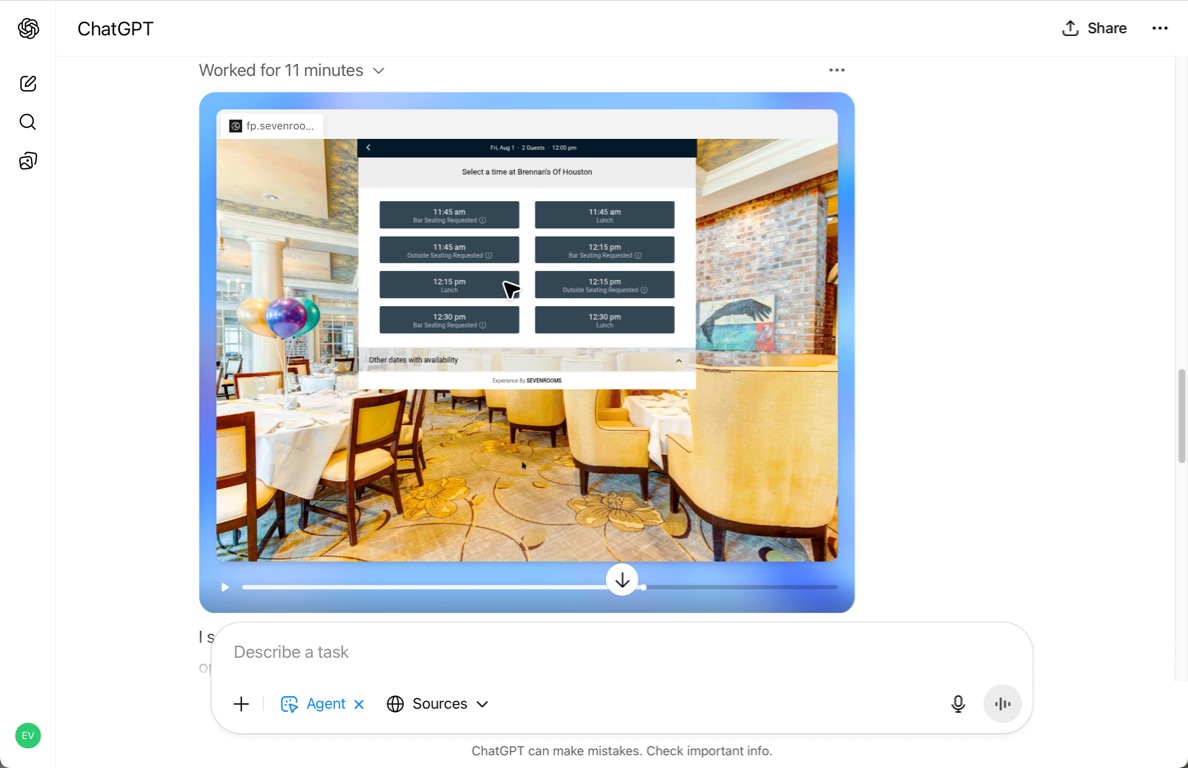

Second, ChatGPT had some difficulty manipulating the dropdown time selector. It had trouble scrolling the list to make 12:00 PM visible within the viewport, and then mis-clicked 12:15. To ChatGPT’s credit, it noticed the mistake and clicked 12:00 PM instead, but the agent might experience some challenges, or at least slowdown, with some selector-control implementations.

Third, when the search results returned possible reservations, 12:00 PM was unavailable. ChatGPT then decided to select a 12:15 timeslot instead and warn me about the change. It even correctly noted alternatives at 11:45 AM and 12:30 PM, too, but if noon had been a firm requirement, then this process would have, again, had to make a big, slow detour.

Finally, and most impressively, ChatGPT accounted for the shellfish allergy successfully. It identified dietary restrictions as the appropriate option in the booking form and selected the appropriate choice. I didn’t intentionally specify which guest had the allergy, so it defaulted to me.

ChatGPT handled the ambiguity and was able to select from an unconventionally styled array of toggle-switch controls. The modal window containing these controls also used unconventional positioning of the Cancel and Save buttons (at the top of the window’s frame instead of the bottom). Could this mean that agents might be less affected by unintuitive designs than humans? Could there be designs that stymie agents but remain usable for humans? The similarities and differences will be intriguing to explore in the future.

Step 5: Enter Details with Human Intervention

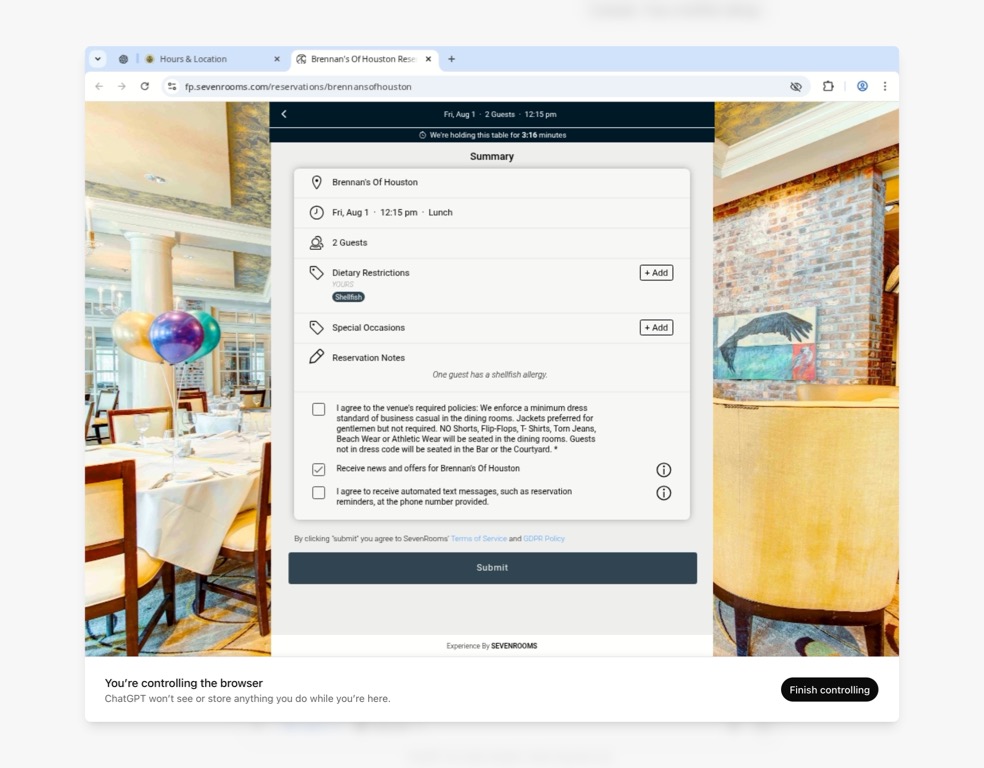

Next, ChatGPT correctly identified that I needed to complete the remaining portion of the web form since it involved personal information that I had not previously provided. In agentic AI, this referred to keeping the “human in the loop.”

Human-in-the-loop is an agentic AI design strategy that aims to keep humans actively involved in decision making, instead of letting the agent make choices and act autonomously.

The “takeover” process was straightforward, but the web-browser window was seemingly low-resolution. I couldn’t find a way to resize it, but I was able to enter the necessary details.

Step 6: Submit Reservation

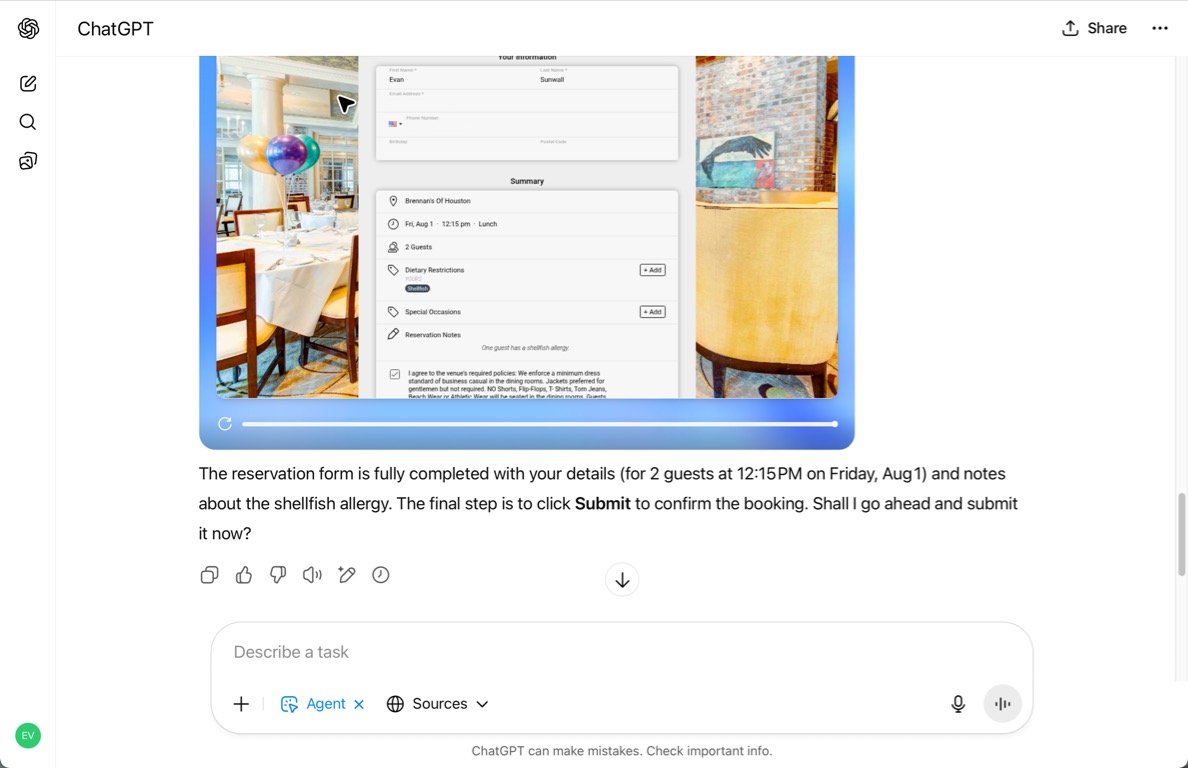

Once I handed back control to ChatGPT, it took a minute to review the completed form and then ask me Shall I go ahead and submit [the reservation] now?

Once again, ChatGPT was effectively keeping the human in the loop at a decision gate.

Decision gates are points where an agentic AI requests confirmation from a human before taking significant actions with potential adverse consequences.

Step 7: Confirm Reservation

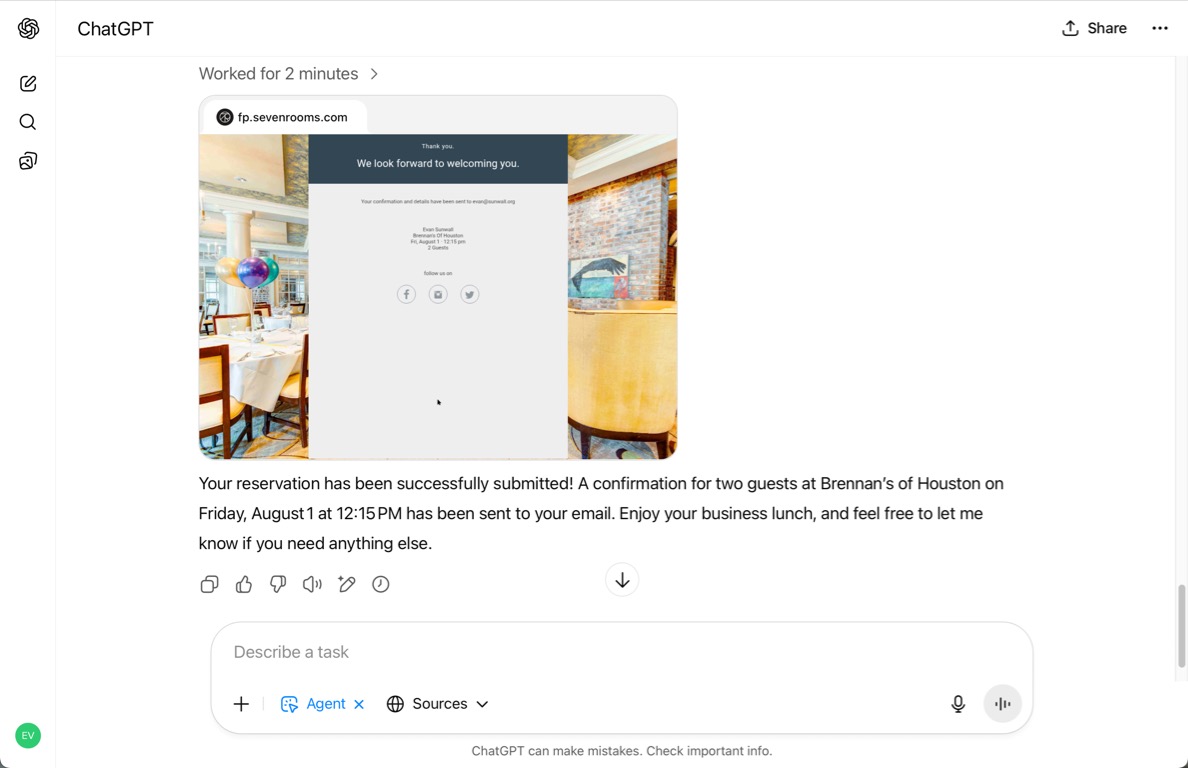

Once permission was given, ChatGPT took another 2 minutes to submit the form and confirm the reservation.

ChatGPT recognized that the reservation window had technically expired, which may have slowed its processing, but the restaurant website was seemingly quick and responsive otherwise, so the delay was probably with ChatGPT.

Overall: It Worked, But Beware the Caveats

With the reservation confirmation in my inbox (that sadly will have to be cancelled even though it’s a nice restaurant), ChatGPT’s agent mode was successful. Despite being given a weak user prompt, ChatGPT performed some research, found a suitable restaurant, prepared the reservation, and successfully submitted and confirmed it.

But the process was very slow, and it’s important to notice the shaky ground it rests on. Some early probing by ChatGPT could have revealed critical information, such as a food allergy, that might have altered the entire trajectory of the chat.

While it surfaced some useful information, it hewed too heavily on the initial prompt and not enough on the practical details that a restaurant patron would need to know to make an informed dining decision. Pivots and dead ends, like a restaurant that is over budget, serves incompatible food, or is unavailable, would have incurred even more delays.

The halting process over a simple web form implies that more complex experiences would be more error-prone and slow. Plus, any agent handling payment or personal information must keep the user in the loop. While this practice mitigates serious errors, it also erodes the agent’s value proposition, and there’s no guarantee that the agent will correctly identify these situations to begin with.

Conclusion

Although just a single anecdotal experience, this author sees ChatGPT’s agent mode as an impressive milestone. But to handle the rigors of everyday use, this agent mode will need to be more inquisitive, much faster, and demonstrate reliability over the long term. Still, we’re entering a new era of computing where machines are becoming fellow users alongside humans.