How do sperm swim? How do they navigate? What is sperm made of? What does a World War Two codebreaker have to do with it all? The BBC untangles why we know so little about this mysterious cell.

But much about this epic journey – and the microscopic explorers themselves – remains a mystery to science.

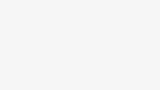

Using newly developed methods, scientists are now following sperm on their migration – from their genesis in the testes all the way to the fertilisation of the egg in the female body. The results are leading to groundbreaking new discoveries, from how sperm really swim to the surprisingly big changes that occur to them when they reach the female body.

“Sperm – or spermatozoa – are ‘very, very different’ from all other cells on Earth,” says Martins da Silva. “They don’t handle energy in the same way. They don’t have the same sort of cellular metabolism and mechanisms that we would expect to find in all other cells.”

Sperm are also the only human cells which can survive outside the body, Martins da Silva adds. “For that reason, they are extraordinarily specialised.” However, due to their size these tiny cells are very difficult to study, she says. “There’s a lot we know about reproduction – but there’s a huge amount that we don’t understand.”

Alamy

AlamyOne fundamental question that remained unanswered over almost 350 years of research: what exactly are sperm?

“The sperm is incredibly well-packaged,” says Adam Watkins, associate professor in reproductive and developmental physiology at Nottingham University in the UK. “We typically thought of the sperm as a bag of DNA on a tail. But as we’ve started to realise, it’s quite a complex cell – there’s a lot of [other] genetic information in there.”

Almost 200 years later, in 1869, Johannes Friedrich Miescher, a Swiss physician and biologist, was studying human white blood cells collected from pus left on soiled hospital bandages when he discovered what he called “nuclein” inside the nuclei. The term “nuclein” was later changed to “nucleic acid” and eventually became “deoxyribonucleic acid” – or “DNA”.

Since then, our understanding of sperm has moved on leaps and bounds. But much still remains a mystery, says Watkins. As scientists have started to better understand early embryonic development, he adds, they are realising that sperm doesn’t just pass the father’s chromosomes on, but also epigenetic information, an extra layer of information that affects how and when the genes should be used. “It can really influence how the embryo develops and potentially the lifelong trajectory of the offspring that those sperm generate,” says Watkins.

Sperm cells begin to form from puberty onwards, made in vessels within the testicles called seminiferous tubules.

“If you look inside the testes where the sperm are made, it starts as just a round cell that looks pretty much like anything else,” says Watkins. “Then it undergoes this dramatic change where it becomes a sperm head with a tail. No other cell within the body changes its structure, its shape, in such a unique way.”

After ejaculation, each of these tiny cells must propel themselves forward (alongside their 50 million competitors) using their tail-like appendages to swim for the egg. And while you may have seen plenty of videos of tadpole-like sperm swimming around, in fact scientists are only just beginning to understand how sperm really swim.

Alamy

AlamySpermatozoa which are healthy and take the right route are rare. Many take a wrong turn in the maze that is the female body – and never even make it near the goal line. For the ones that do find their way to the fallopian tubes, scientists think that they may be guided by chemical signals emitted by the egg. One recent theory is that sperm may use taste receptors to “taste” their way to the egg.

Once the sperm find the egg, the challenge is not over. The egg is surrounded by a triplicate coat of armour: the corona radiata, an array of cells; the zona pellucida, a jelly-like cushion made of protein; and finally the egg plasma membrane. The sperm cells have to fight their way through all the layers, using chemicals contained in their acrosome, a cap-like structure on the head of a sperm cell containing enzymes that digest the egg cell coating. However, what prompts the release of these enzymes remains a mystery.

Human cells are diploid. This means they contain two complete sets of chromosomes, one from each parent. If more than one sperm were to fuse with the egg, a condition called polyspermy would arise. Nondiploid cells – ones with the incorrect number of chromosomes – would develop, a condition lethal to a growing embryo.

To prevent this from happening, once a sperm cell has made contact with it, the egg quickly employs two mechanisms. First, its plasma membrane rapidly depolarises – meaning it creates an electrical barrier that further sperm cannot cross. However, this only lasts a short time before returning to normal. This is where the cortical reaction comes in. A sudden release of calcium causes the zona pellucida – the egg’s “extracellular coat” – to become hardened, creating an impenetrable barrier.

One way researchers are hoping to shed light on sperm is by studying species other than our own, says Scott Pitnick, a professor of biology at Syracuse University in New York. Human sperm cells are microscopic, so we can’t see them with the naked eye. But some fruit fly species produce sperm cells 20 times their own body length. That would be like a man producing sperm the length of a 40m (130ft) python.

“Why do males in some species make a few giant sperm?” asks Pitnick. “The answer, it turns out, is because females have evolved reproductive tracts that favour them.” That’s “not really much of an answer”, he adds, because it’s just the redirects the question: why have females evolved this way? “We still don’t understand that at all.”

But it does teach us that sperm as they exist in the male body is only half the story, says Pitnick. “There’s a massive sex bias historically in science. There’s been this obscenely biased male focus on male traits. But it turns out that what’s driving the system is female evolution – and males are just trying to keep up.”

“It turns out the female reproductive tract is this incredibly, rapidly evolving environment,” says Pitnick, “and we don’t know much about what sperm do inside the female. That is the big, hidden world. I think the female reproductive tract is the greatest unexplored frontier for sexual selection, theory and speciation [the process by which new species are formed].”

The fruit fly’s long-tailed sperm, suggests Pitnick, could be considered an ornament – much like a deer’s antlers or a peacock’s tail.

Ornaments are a “sort of a weapon in evolution”, explains Pitnick. More than just a defence from predators, ornaments like antlers and horns often have two roles to play. “A lot of these weapons are about sex, and usually male-male competition. The [fruit fly’s] long sperm flagellum really meets the definitional criteria of an ornament. We think the female tract has traits that bias fertilisation in favour of some sperm phenotypes over others.”

We know a lot about pre-mating sexual selection, Pitnick says. “Say, it’s prairie chickens dancing out on a grassland, or a bird of paradise displaying in a rainforest. It’s motion, it’s colour, it’s smells?” Processing this sensory input, explains Pitnick, leads to decision making – whether the pair mate or not.

But, Pitnick says, the sexual selection that goes on inside the female after mating – and how this drives the evolution of sperm – largely remains a mystery. “We still understand very little about the genetics of ornaments and preferences,” he says.

Alamy

AlamyTo fully understand sperm, we need to think about how the entire lifecycle of the sperm – and the female body, explains Pitnick, plays a huge role in the sperm’s development. “Sperm are not mature when they finish developing in the testes, they’re not done developing.” Complex – and critical – interactions occur between the sperm and the female reproductive tract, he says. “We’re now spending a lot of time studying what we call post-ejaculatory modifications to sperm across the whole animal kingdom.”

According to a 2023 report published by the World Health Organisation (WHO), around one in six adults worldwide experience infertility – and male infertility contributes to roughly half of all cases. (It’s also worth noting that many people around the world are not having as many children as they want for other reasons too, such as the prohibitive cost of parenthood, as a recent United Nation population Fund report highlighted).

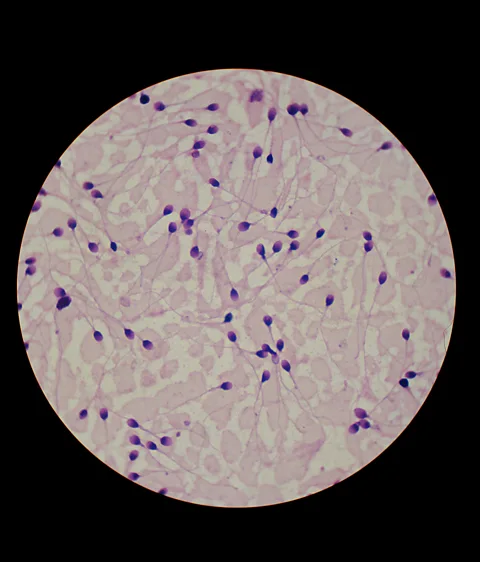

“With all those moving parts, there are so many things that could go wrong,” says Hannah Morgan, a post-doctoral research associate in maternal and fetal health at the University of Manchester, UK. “It could be a mechanism: it doesn’t swim very well, so it can’t get to the egg. Or it could be something more intricate within the head of the sperm, or other regions of the sperm. It’s so specialised in so many different ways, that lots of little things can go wrong.”

One way to see if a man may be infertile is to look inside the sperm, says Morgan. “How does the DNA look? How is it packaged? How fragmented is it? To break open the sperm, there’s a whole range of stuff you could look at. But what is a good or bad measurement? We don’t actually know.”

Perhaps by unravelling the mystery of sperm and how they function, Morgan says, we might begin to understand male infertility too.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram.