Josh Safdie grew up playing table tennis with his father. While on this week’s episode of the Filmmaker Toolkit podcast, the “Marty Supreme” co-writer and director talked about how he was drawn to capture the feeling of playing the sport.

“I had ADD, so I played it a lot as a kid, and it takes an intense focus, and the frustration when you lose that focus is heightened, and the precision that it takes,” said Safdie. “So I was trying to match that.”

Safdie was drawn further into the idea of making a film about the sport when he learned about its early days in post-WWII New York City. Through research with his wife, producer Sara Rossein, and listening to stories from his uncle George, who hung out at Lawrence’s Table Tennis Club (lovingly recreated by production designer Jack Fisk in the film) in its heyday with top players like Marty Reisman (the inspiration for Timothée Chalamet’s Marty Mauser character), Safdie discovered the ecclectic cast of characters who gravitated toward the sport in the 1950s.

Ping-pong was a perfect sport for his fleet-footed, quick-witted protagonist — Safdie even learned there was a long, well-established history of people with high IQs, who did poorly in school, drawn to the sport. That ping-pong wasn’t taken seriously was perfect for Safdie’s desire to tell a story of the unbridled ambition of post-war American individualism — that Marty believed it was his calling to ride the disreputable sport to fame just meant it would be an even lonelier road, lined with doubters.

There was also something inherently dramatic about the sport. Said Safdie, “ It’s fast, and it’s a dialogue between two people in close proximity to one another.” But was it cinematic? Or, more to the point, was it too fast a sport to be effectively incorporated into the storytelling the way Safdie, an ardent cinephile and sports fan, had watched other great directors do with boxing? While the intense back-and-forth rhythm and strategy of ping-pong was appealing, Safdie would learn that, when played at the highest levels, there’s less than one-third of a second (seven film frames on average) between ping-pong shots.

“That was a real fear,” said Safdie. “It’s a challenging sport. There’s really only one way to show it, if you’ve watched it professionally: It’s three-quarters from the back to understand the chess-like quality of it.”

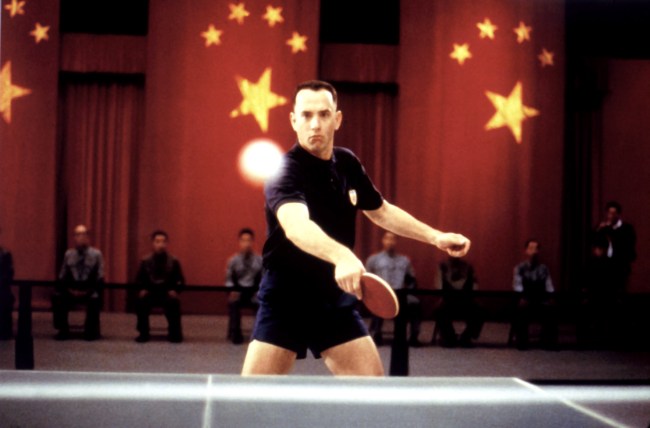

As Safdie’s dream of making “Marty Supreme” became a reality, he said the unanswered question of how he would film the matches terrified him most. “ So I went and searched ‘“Forrest Gump” choreographer table tennis’ because as a kid that was my favorite parts of that movie,” said Safdie. “I loved it because it’s about an amazing true story about ping-pong diplomacy, which was inspiring [for ‘Marty Supreme’], too.”

The director learned all roads led to Diego Schaaf, who, along with his wife Wei Wang (a Chinese-born American table tennis player who represented the U.S. at the 1996 Olympics), developed the niche of being Hollywood’s preeminent table tennis experts, working with filmmakers and trained actors on everything from “Friends” to “Balls of Fury,” and yes, “Forrest Gump.”

“I met with Diego,” said Safdie. “I was like, ‘Well, Timmy’s kind of a basement player. He’s been training now for a couple of years, he’s gotten better, but I don’t know.’ [Schaaf said], ‘Don’t worry, we can do this.’”

What Safdie loved about Schaaf was beyond being a great technical advisor; he was a historian of the sport. It was something the director took full advantage of in their first collaborative step: choreographing the “Marty Supreme” matches.

“Diego had this incredible library and encyclopedic knowledge of the games, and we had to build these points, Frankenstein them, using real ones. So if you saw the visual script, one point could be from six different games over the course of 50 years. It’s a really beautiful document so that Timmy and Koto [Kawaguchi] could study the choreography and learn how to play those points in real life.”

For Chalamet and Kawaguchi — who portrays Marty’s rival Koto Endo, and in real life is the winner of the Japanese National Deaf Table Tennis Championships — learning the foot-and-paddle choreography, with the precision of dancers in a Bob Fosse musical, was vital. Yet, as much as Chalamet’s training with Wang increased, and his game improved, the reality set in that CGI would have to be used — with Schaaf telling Safdie, “10-time gold medalists won’t be able to do what you want them to do.”

“A real point has incredible nuance. It’s improvised. Because the ball can bounce here and Timmy’s not going to know how to respond to it. He might lose the point when he’s supposed to win it,” said Safdie. “Timmy obviously wanted to play the points for himself, ‘I need to be able to play all the points with the real ball.’ So every time we would entertain [that], we would do it, and it was great because we would use shots where he’s using the real ball, but then to get the proper coverage that I needed to have the precision that would come with placing the ball.”

“Placing the ball” meant CGI visual effects, with Chalamet and his opponent pretending to play without a ball. Safdie was surprised that the physical demand on Chalamet, Kawaguchi, and the other players pretending to hit a ball was actually more complicated than doing it for real — getting the paddle position, spin, and velocity without actually hitting a ball was demanding.

“It was harder than playing the points for real because the timing has to be perfect: seven frames between hits if you’re going to put a ball in [play]. And I was petrified of it because [Schaaf] told me they can only do one point at a time,” said Safdie. “To me, it was essential for their performances to be able to play at least three in a row, so they could feel the rhythms, for all the hundreds and hundreds of extras to be able to get into the game, and have the ebbs and flows of the narrative. I was really afraid of being able to not only cover it in the ways that I wanted to, but I’d have the amount of takes that I’d want for performance, and I’d be able to have a longevity of takes, so I could capture the nuances of the in-between parts, like when a boxer is sitting against the ropes. So I was really afraid of it.”

The way Safdie dealt with his fear was to over-prepare, and he asked a willing Chalamet to do the same. Safdie had the comfort of working with “Uncut Gems” visual effects supervisor Eran Dinur once again, but to a degree he had never come close to in his 17 years as a professional filmmaker, which became vital for him to pre-plan exactly what he wanted.

“Uncut Gems” cinematographer Darius Khondji was also back for “Marty Supreme.” He would shoot the ping-pong matches in a documentary-like, multiple-camera way, finding a way to break being solely reliant on the three-quarter angle of professional table tennis broadcasts, and getting shots straight down the barrel of a match by positioning the camera behind the players and capturing the sense of the ball coming toward the camera lens.

For Safdie, the over-preparation was all in the name of “dignifying the sport and wanting to capture the feeling of [playing] it.” That he pulled it off was both a relief and his proudest filmmaking accomplishment.

“Marty Supreme” is now playing nationwide.

To hear Josh Safdie‘s full interview, subscribe to the Filmmaker Toolkit podcast on Apple, Spotify, or your favorite podcast platform.